A Legacy of Studebakers in Arbuckle

Francee Atran-Gatejen holds an original A.J. Atran Studebaker dealer license plate frame while standing in front of the family’s former garage on 5th Street in Arbuckle.

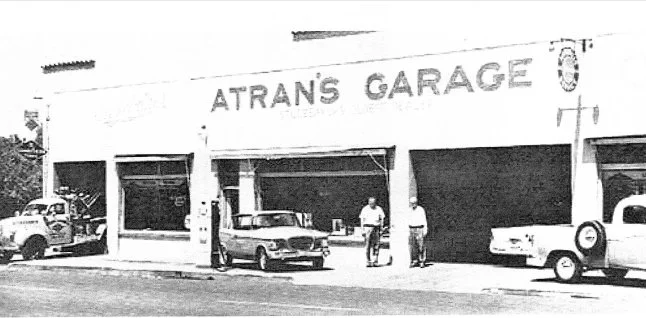

Saturday, began like any other late-summer morning in Arbuckle, quiet streets and a faint hum of almond harvesters shaking their crop. The sound of engines broke the stillness. One by one, gleaming Studebakers rolled into town, their polished chrome catching the sun as they lined up along 5th Street. They had come not just to mark International Drive Your Studebaker Day, but to honor a place woven deep into the town’s past: Atran’s Garage, once the oldest Studebaker dealership.

At 204 5th Street, the facade still bears the weight of its history. In 1889, when Arbuckle was still more farm town than crossroads, Alex Atran opened a blacksmith shop and livery stable on the site. That same year, he became a dealer for Studebaker wagons. When the company expanded into automobiles, the Atran family followed. For the next 75 years, until Studebaker folded in 1964, Arbuckle residents could buy one of those cars without leaving town.

In the early days, selling cars was not simply handing over keys. Dealers were called brokers, and they often taught buyers how to drive. Picking up cars meant long days by ferry and dirt road to San Francisco, crawling along at 25 miles an hour, returning home with orders filled. By the 1930s, automobiles arrived by rail, a sign that Arbuckle was no longer so distant.

Studebaker prided itself on quality, but it came at a cost. In the 1920s, when a Ford or Chevrolet could be had for under $800, a Studebaker cost at least $1,500. Arbuckle residents bought them anyway. The Atran dealership sold roughly 2,500 Studebakers during its run, along with Chevrolets, International trucks, Oliver tractors, and even Packards for a brief span.

Stanley Atran, left, and his grandfather Alex Atran stand in front of Atran’s Garage in Arbuckle in 1959, where the family sold Studebakers for more than seven decades.

The original 1889 building burned, and in 1929 a new structure rose in its place. Its cement showroom floors, as Stanley’s daughter Francee remembers, were difficult to mop but sturdy enough to withstand decades of work.

By 1978, when Stanley was interviewed about selling his business, he said Studebakers were still coming through his bays every day, often brought in by customers who drove from outside the county. Even then, half his business was not local.

When Stanley stepped away, the building did not close. It shifted, changed names and hands, but the heritage was respected. Tony and Dena Luiz bought it and kept the Atran name visible.

“I think they did that out of respect for my dad,” Francee said.

Later owners included Steve and Jan Criner, and businesses from Arbuckle Motor Sales, Hust Brothers, to Ag Depot used the space.

Today it is Mike’s Universal Service, where proprietor Michael Ortiz and his crew keep farm equipment running.

For Francee, that continuity matters.

“I love that Michael is an Arbuckle boy,” she said. “My grandfather and father would be so happy.”

Francee Atran-Gatejen shares memories of her family’s history at Atran’s Garage with members of the Karel Staple Chapter of the Studebaker Drivers Club during a tour of the remodeled facility.

Francee, the youngest of Stanley’s three children, drove in from Elk Grove with her husband Ric to join the Studebaker gathering. For her, the day was less about the cars and more about family and place. She recalled the small house tucked behind the shop where her grandparents first lived, and the larger home they later built across the street. Her own parents built their house next door, which meant her father’s commute to work was nothing more than a short walk across 5th Street.

She recalled her grandmother’s red and black Studebaker Hawk, and her father’s International Scout that carried her to Sand Creek.

“My dad would say, put her hair up in pigtails,” she remembered. “I knew it was going to be a fun day.”

To her, those cars were less machines than threads in the fabric of family life.

She also remembered her father’s insistence that no car left his shop unfixed.

If a customer could not pay, bartering began. She learned to cut butter in the garage after her father came home with 30 pounds of it as payment. On another occasion, she picked apricots to settle someone’s account.

“Once my dad sold a car, it was always his,” she said. “He just wanted your car on the road.”

The town around the garage was part of her story too.

She remembered Arbuckle businesses now vanished: Boyd’s Auto Center, Putnam’s Store, Craft’s Market, Denny’s Hardware, two bars, a five-and-dime, Boles Television Repair, and Max’s Frostie.

“Every senior graduating class, Max and Lyle, the owners of Max’s Frostie, would give us certificates for two meals,” she said.

Her memories stretch beyond town. She spoke of playing among the remains of the German prisoner of war camp that stood near Arbuckle during World War II. Prisoners were brought there to support the nation’s war effort, including experimental rubber production from a shrub called guayule, and labored in almond orchards.

“I used to go out and play at the abandoned camp and climb the towers,” she said.

The site later became apartments known as the Alexander Camp, then demolished to be rebuilt as the Alexander Apartments in the 1980’s. Today the Tim Lewis housing development stands where guard towers once rose.

The Studebaker gathering on Sept. 13, brought those stories back into focus. About a dozen cars lined 5th Street, their chrome and curves reminders of a different time. Members of the Karel Staple Chapter affixed a Studebaker emblem to the headstone of Stanley and CeCelia Atran at the Arbuckle Cemetery, connecting memory to stone. Francee joined them in touring the remodeled building, pointing out where her father’s office once stood, where the showroom hosted conversations and deals.

To the club, it was a celebration of a brand. To Arbuckle, it was a reminder of how a single business tied together families, roads, and decades.

For Francee, it was both personal and communal. She remembered attending a Studebaker dinner in Sacramento in the 1970s, when her father was honored as the oldest dealer.

“I didn’t realize how much it meant to everybody,” she said. “Because I am from the small town of Arbuckle, I thought Studebakers were just here. At that dinner, I understood they were everywhere.”

In Arbuckle, the cars were everywhere too. Generations of families bought them at Atran’s, and people like Shirley Griffin, now deceased, who once pumped gas at the garage, built their first jobs around it.

The story of Atran’s Garage is the story of a town that adapted but never forgot its roots. It began with a wagon, grew into a dealership, and became part of Arbuckle’s identity.

Today, Arbuckle is not the same town that Alex Atran knew in 1889. Stores have closed, farms have modernized, and new families have arrived. Yet the stories linger. Remembering the garage is more than recalling a business. It is about remembering how people lived, how they helped each other, and how a town shaped its own future one trade, one handshake, one car at a time.